Jews Continue to Call the Rural South ‘Home’

Temple Mishkan President Israel Ronnie Leet poses for a photo outside of Temple Mishkan Israel in Selma, Alabama on June 27th, 2021.

Temple Mishkan Israel President Ronnie Leet and congregation member Hanna Berger pose for a photo in Temple Mishkan Israel’s sanctuary in Selma, Alabama on June 27th, 2021.

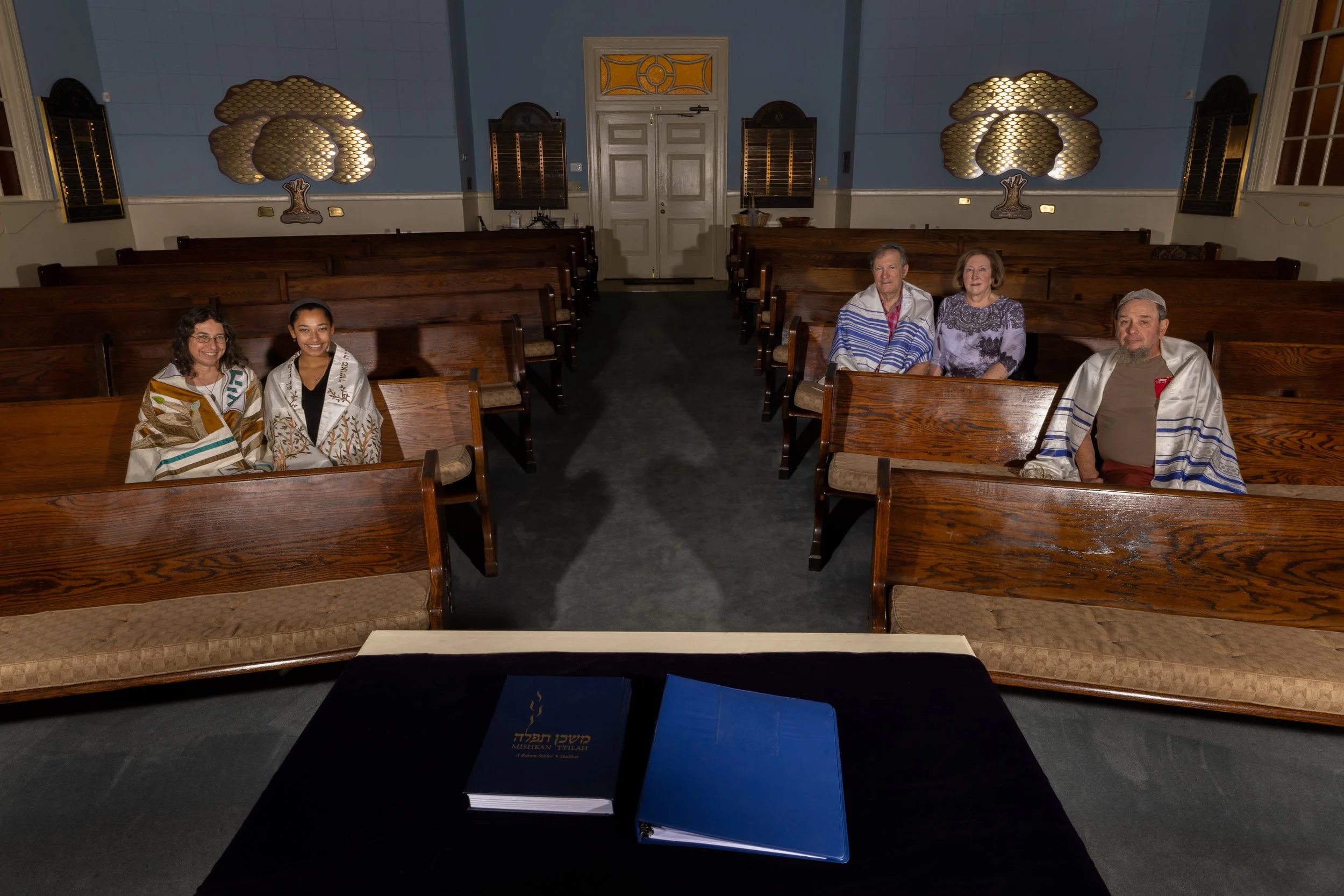

Members of Congreegation Rodeph Sholom, from left to right, pose for a group photo in the synagogues sanctuary on August 21st, 2021 in Rome, Georgia: Anne Lewinson, Miriam Loya, Jeffrey Brant, Nancy Brant, and Rich Chanan

Miriam Loya, who is a sophomore in high school and is one of the few children in congregation Rodeph Sholom, poses for a portrait in the synogague's sanctuary on August 21st, 2021 in Rome, Georgia.

Nancy Brant, current president of Rodeph Sholom, and her husband Jeffrey Brant, former president, pose for a portrait in the synogague's sanctuary on August 21st, 2021 in Rome, Georgia.

Congregation Rodeph Sholom is seen on August 21st, 2021 in Rome, Georgia.

Across the rural South, Jewish communities are springing up, dying out and surviving. This series, a combination of portraits and interviews, explores contemporary Jewish life, with a focus on Jewish individuals and communities in towns with populations of less than 50,000. The two synagogues I visited for this first installment are long-established but are fighting to continue to serve their communities.

In Selma, Alabama, a city known for its civil rights history, the town and Temple Mishkan Israel have both seen its headcount drop heavily since the 1960s. With only three active members, the community works to maintain the 120-year-old synagogue building and tries to educate those who visit the community.

Across the state border in Rome, Ga., Rodeph Sholom has had a long and friendly history with the surrounding community, but continues to face anti-Semitism as they try to preserve their historic congregation. They are also combating the loss of younger generations who have moved away from the northern Georgia town.

A few blocks away from the bridge where John Lewis was beaten on Bloody Sunday, past pharmacies and stores that mark the names of Jewish owners long since passed, sits Temple Mishkan Israel, a beautiful building in Selma that was once a spiritual home to over 500 community members. The stained-glass windows and ornate bimah and ark, which still contains Torahs for visitors to use for services, are part of the 121-year-old building. While there are no longer weekly services at the temple, members continue to maintain the sanctuary and hope to repair the roof and turn the building into a museum. Ronnie Leet, president of the synagogue, was born and raised in Selma before heading to college — the only four years he’s left town — and has been working on this mission over the past few years along with other community members.

For almost a century from the time Temple Mishkan Israel was founded in 1867, the Jewish community flourished. Between 350 and 450 Jews lived here in the early 1940s, per Leet, with “most of the businesses downtown” being Jewish-owned. Hanna Berger, another member of the synagogue, was born in Selma and never expected to return permanently, something she said is common: “It’s a typical story, not only in Jewish communities, but immigrant communities in general, that people come in, and they start businesses and try to build a life … and by the third generation, the children don’t want to run their store.” Leet was one of the few who came back to help run his family’s business in Selma, but said that he was only one of three young people “of a thriving Jewish community … that came back.” Yet even now, he feels his connection to Judaism has strengthened over recent years: “I feel more connected than I ever have. … I stay connected through this building, through different venues, that I can learn more about.”

The synagogue was central to the community, with non-Jewish members often attending services. Berger described the decades during which she grew up in the ’40s and ’50s: “At Friday night services, there were always some guests and some kids … who were not Jewish and [we] would go to church services with their friends. … It was small as cities go, but it really was active, and we felt we were part of the [Selma] community.”

By the early 1970s the congregation no longer had a full-time rabbi. Like many rural Jewish communities, it began to rely on “traveling rabbis” and eventually moved on to student rabbis, before dropping the tradition of an “in-house” rabbi completely.

In 1997, there was a reunion of the families and their descendants, called “Home for the Holidays,” which brought over 220 people back to the synagogue, including many descendants who had never been to Selma before, per Leet. This sort of national network for the congregation is helping the synagogue transform itself, as the community has come together to help with repairs to the roof and the overall maintenance of the building. “It proved a point, people love their roots,” Leet said. “They love Selma, and they love this temple.” Even with this support, however, the few remaining community members have had to work hard to continue worshipping. Member Steve Grossman ran services after the congregation could no longer support a student rabbi, but that came to a halt after Grossman was tragically killed in a car accident.

Many southern Jewish communities now find themselves in the same boat as the one in Selma, with long-standing communities continuing to shrink. In Rome, Ga., Congregation Rodeph Sholom still holds services, now on Zoom, for its relatively small membership. Founded in 1875, the congregation had full-time rabbis until 1955, then relied on student rabbis from Hebrew Union College for the following 40 years. Nowadays community members and visiting rabbis help conduct services at the Reform congregation. The synagogue, now headed by President Nancy Brant, has a core group of around 15 to 20 members who participate in services and activities through the congregation, as well as a “huge mailing list,” per Brant. The synagogue also has an active brotherhood and sisterhood, and a religious school run by congregation members, although currently there are no students that would attend.

The synagogue was built on land purchased from the neighboring St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in 1938, a small part of a long and friendly history between the two places of worship. While the synagogue doesn’t hold many large services, with the exception of Passover and b’nai mitzvah celebrations, the church allows the congregation to use their larger social hall. After the shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue, hundreds of community members attended services at the congregation, and local religious leaders spoke. So many came, in fact, that the service hall was full, and the ceremony had to be telecast.

While the Rome community has been supportive and friendly to their Jewish neighbors, and the congregation itself, there has also been a fair share of harassment. There was the nearby Klan rally in 2016, which congregants protested, as well as anti-Semitic papers plastered on the door of the synagogue in previous years, along with other small threats and acts of intimidation. Anne Lewinson, a congregant and professor at Berry College, believes these acts aren’t representative of the Rome community: “I do think there’s a fair bit of ignorance … a lot of people just don’t know that a Jewish community exists.” The wider community has also been accepting of Jews, at least in Miriam Loya’s experience. The daughter of Lewinson and her Muslim husband, Miriam attended the synagogue’s school when it was in operation and is now a sophomore at Rome High School. For her bat mitzvah, she invited her entire class to the service, recalling that “even though they didn’t really know what was going on at all and didn’t understand what’s happening … they were very welcoming.” Loya is open about her religion to classmates, and finds that they are often “curious,” as “most of them don’t really know what [being Jewish] means.”

Althoguh the congregation has been able to host services, and has a very active group of members, they find that they are sometimes taking unique measures to maintain the kinds of programming on offer at larger synagogues. Lewinson’s son, Matt, was trained for his bar-mitzvah by a rabbi, but in the following years he’s had to train the next generation. Small rural synagogues like Rodeph Sholom often rely on their members to maintain the building and services, and to help keep the community alive, Lewinson said: “If anybody was going to teach the religious school kids, it was going to be members of the community; if anybody was going to sweep up after an event, it was gonna be members of the community.”

As the Brants and Lewinsons have come in the past two decades, some of the community’s older members continue to attend. Rich Chanan, the son of a Holocaust survivor, moved from a heavily Jewish area in New York, and has been at the congregation since 1985. Coming from a place with a high concentration of Jews, he quickly found that the “Jewish culture was minimal” here, compared to where he grew up. Chanan has also found that the ignorant can be dealt with: he’s had a Klan member re-wire his house while having a full conversation around the actuality of Jews as compared to the myths that circulate. He follows the work ethic that his father, a survivor of Bergen-Belson, taught him: “If you showed you could do every kind of work you were assigned before the guards, the guards respected you and preserved you. Sometimes they will not beat your head as hard. They’ll give you some extra food to take home.” But he also believes in the importance of not backing down. In his time at the synagogue, “there has been a dismal reduction in the crowd,” and he is worried about the fact there are so few children left in the congregation.

Others are more optimistic about the congregation’s future. Nancy Brant said, “there are people that used to be here, and used to have family here, who still support us monetarily,” which helps the congregation maintain security and programming it would not otherwise be able to afford. Jeffrey Brant, Nancy’s husband and a former president of the congregation, eloquently explained the situation around the issue of building maintenance: “People ask, why do you keep having this building with only a few people here? We want to keep the Jewish community going here as much as we can. … And it’s not so much the financial stuff; it is just that we need members and we need the people.” Nancy Brant likes to call their congregation “the little temple that could,” an apt name for a synagogue that continues to serve Jews in the heart of rural Georgia.